In a culture — both film-going and overall — that undeniably dismisses intellectualism, there’s a reviving thing about a film where a key plot guide spins around a person’s capacity toward precisely evaluate a piece of old Greek model. “An Injured Grovel” is a film that praises workmanship and craftsmanship history, one that arrives at back across the centuries for motivation takes out imagery that actually resounds today. You can call it pompous assuming that you should. Be that as it may, don’t call it stodgy.

The third movie from essayist/chief Travis Stevens (“Jakob’s Better half,” “Young lady on the Third Floor”) is produced in fire and blood, taking his eye for striking visuals and hoisting it to hallucinogenic new levels. Stevens’ essential stylish standard for “An Injured Grovel” is ’70s grindhouse film, with all its coarseness, grain, and loaded orientation governmental issues. This is crossed with the serious pools of brilliant variety promoted by Dario Argento, and joined with the odd sensibilities of Francisco Goya’s “Dark Artworks.” The consolidated impact is one of hot visualization.

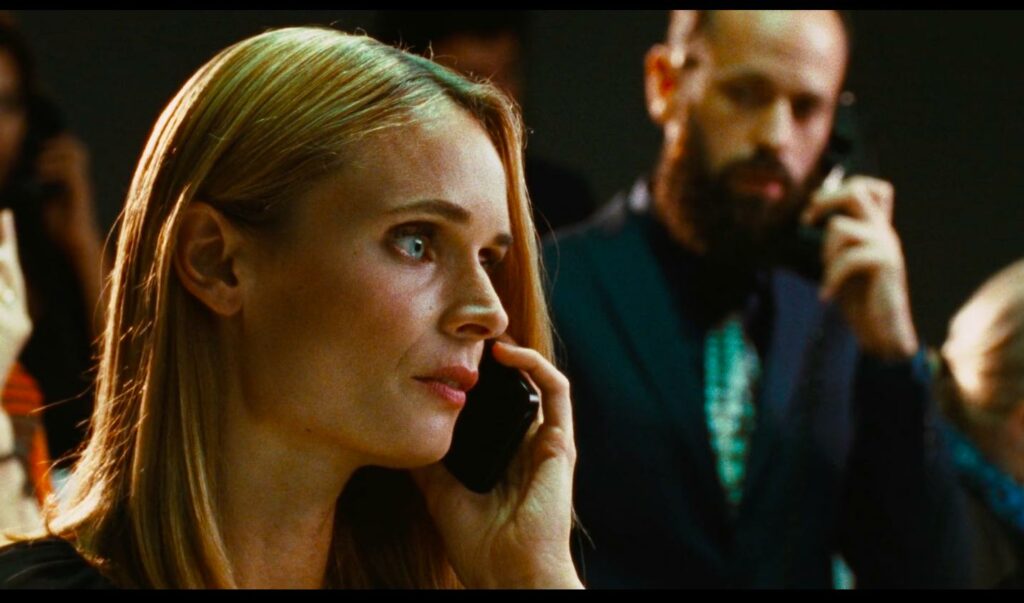

The driving feeling behind this right in front of you style is all displeasure — explicitly, ladies’ equitable fierceness towards misanthrope powers of viciousness and abuse. These are typified as Bruce (Josh Ruben), an apparently decent person about whom exhibition hall custodian Meredith (Sarah Lind) is feeling better after a small bunch of dates. The crowd realizes that Bruce is terrible news when Meredith consents to go with him upstate for a heartfelt end of the week in the country: In a virus open, we’ve previously seen Bruce tail and cut a workmanship seller in quest for “The Rage of the Erinyes,” an exceptionally old piece of figure portraying the three Wraths of Greek folklore. Presently we’re only trusting that Meredith will get up to speed.

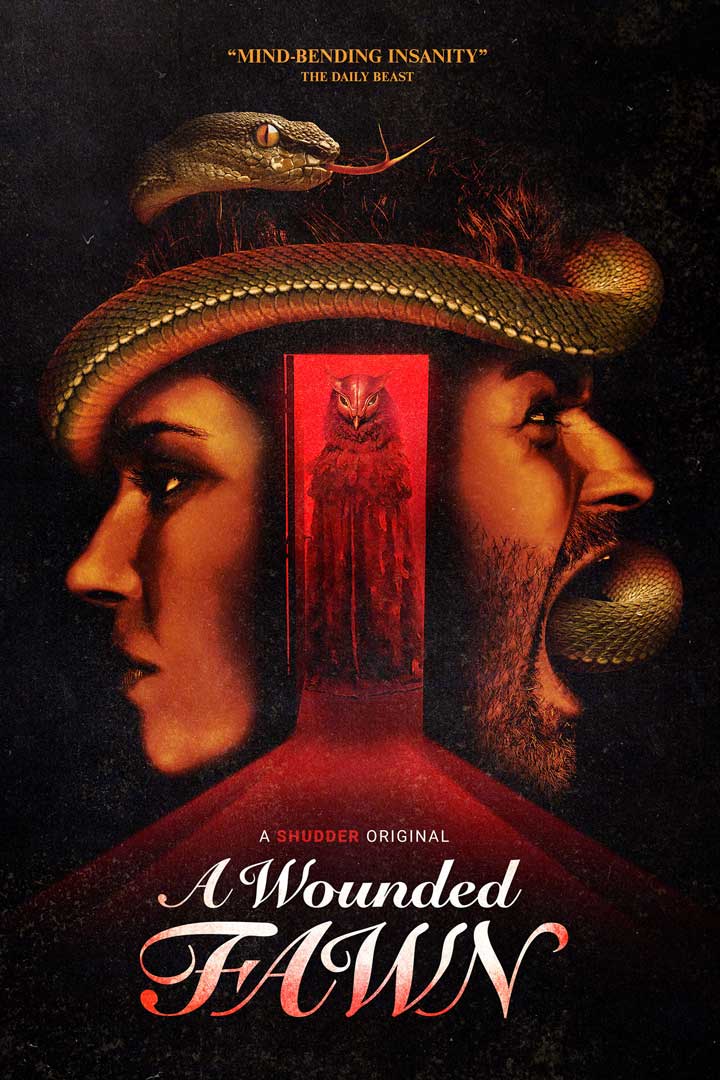

A misanthropic psycho killing a lady to claim a sculpture addressing female fury is emblematically stacked with the eventual result of being spot on. Fortunately, the retribution is comparably baldfaced. In its most memorable a portion of, “An Injured Grovel” unfurls like a brilliant, yet not especially weighty sequential executioner thrill ride. In its second, it turns out into something strange and unforeseen as Bruce gets powerful proper recompense for his numerous wrongdoings. This, obviously, is fulfilling to watch. In any case, makes it truly fascinating that it’s never obvious how much these yelling shrews are coming from Bruce’s own psyche.

At the film’s midpoint, the tone shifts from lean and frightful to ranting and vainglorious. The legendary substances that have so far floated behind the scenes of the story transform into flesh characters as the three Wraths — Tisiphone, Alecto, and Megaera — appear, articulating in booming voices about the harm they’re going to cause for this unfortunate misuse of oxygen. Add a human-sized owl, its steampunk acolytes, gallons of red-orange blood, and heaps of mysterious imagery, and “An Injured Grovel’s” transformation from a rough caterpillar into a similarly vicious, however endlessly more odd butterfly is finished.

On occasion, the back portion of the film falls off like a cutting edge theater creation, or perhaps a lot of Shakespearean entertainers high on hallucinogenics — think individuals enclosed by bedsheets absorbed counterfeit blood going through the forest shouting about rage. Be that as it may, the minutes when “An Injured Grovel’s” low-spending plan creases start to show don’t demolish the film. There are several explanations behind this: First is Stevens’ shrewd hug of grindhouse feel. Those films were undeniably kept intact with conduit tape, as well, so the unpleasant edges improve the impact.

Second is the lead entertainers’ obligation to their jobs. Lind is a power of nature as Meredith, energized by a heavenly breeze that pushes her forward with the sureness of a Valkyrie riding a horse. Also, Ruben gamely bites the bullet, especially in a drawn out credits grouping that impeccably summarizes the film’s mix of silliness, dauntlessness, and equitable displeasure. In his past work, Stevens messed with class shows. Here, he breaks them into 1,000 pieces.

Leave a Reply